INMA initiative leads do deep dive on 3 key topics at Media Innovation Week

Conference Blog | 06 October 2024

Key industry areas of interest by media leaders attending INMA Media Innovation Week required a deeper dive: reader revenue, newsroom organisation and transformation, and Big Tech.

To cover those topics with the 337 attendees in Helsinki, INMA initiative leads — Readers First Initiative Lead Greg Piechota, Newsroom Transformation Initiative Lead Amalie Nash, and Digital Platform Initiative Lead Robert Whitehead — lead breakout groups during the week.

Here’s a summary of the discussions:

Reader revenue case studies from Europe

Several case studies focused on brand, paywalls, optimising user journeys, data.

“Transformation, it is about different format features but basically be ready for a marathon,” INMA Readers First Initiative Lead Greg Piechota said about the session. “Subscriptions it not a sprint.”

Personalised paywalls: News companies with paywalls have 38.7% more subscribers.Tim Rowell, senior vice president/global pubishing at Piano UK, said, urging reader personalisation of paywalls: “We’ll let this reader keep reading because they’ll generate ad revenue so we won’t let them hit the paywall. Another is likely to subscribe and not likely to bring in ad revenue so we’ll hit them with a paywall immediately. The group in the middle is really important, and it’s 50% of your audience. Test, play around with the model to understand how to push them to advertiser revenue and digital subscriptions.

Digital product at Keskisuomalainen: The challenge was to turn free newspaper into a subscription-based digital product. A paywall worked, growing monthly subscriptions by 21% and reaching 171,000 on digital channels. The journalism is now deeper, more current “because the business model challenges us to make better content,” said Kirsi Hakaniemi, digital transformation lead at the company.

User needs model at Mediahuis Noord: When a man in the northern part of The Netherlands shot and killed a couple, confessing to the crime on Facebook live, the nation was shocked. Mediahuis Noord took this as a learning experience in user needs. What they weren’t doing is filling the “help me” user need, Alwin Wubs, newsroom analyst at the company, said. “We published an article called, ‘Here’s what we know about the drama in Weiteveen,’ updated it regularly with bullet points. It was prominently positioned.” This resulted in a significant number of subscriptions.

Tooltip at Der Spiegel: Tooltip is a tool used to engage readers after they subscribe. The interactive tool guides readers through Der Spiegel’s options and is a premium onboarding experience. “We saw an uplift of 9% in engagement after 30 days,” Jakob Halm, engagement manager, said.

Young subscribers at FAZ: The challenge was to increase brand recognition among 25- to 35-year-olds, of which only 40% new of the brand. The campaign included more social, niche topics, and a 50% off offer. Quickly, brand recognition increased to 70% among this target grip. Brand awareness increased by 263% and conversion rate improved by 391%.

German media subscription partnership: Alles.plus is a collaboration of large media companies in Europe, including Der Spiegel and FAZ. Content from member news publishers is available across brands in a bundle for consumers. Although testing is new and results are not available yet, “we really want to make sure the experience works — that the customer gets what he/she wants and the subscription works,” said Isabella Wohlwend, head of subscriptions at Der Spiegel.

LLMs and media: ensuring fair compensation for content creators

The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) mirrors previous technological shifts, where the balance of power between content creators and platforms has always been a delicate one.

While LLMs offer significant potential, they also raise concerns, particularly for industries like journalism, which depend on content ownership and distribution.

“We have been here before,” said Robert Whitehead, Digital Platform Initiative lead at INMA, reflecting on the familiar pattern tech companies follow when working with media.

According to Whitehead, these companies initially rely on media to get the content they need but, over time, focus more on serving their audience, leaving media companies behind.

“First, they need us to get started and we provide the content,” he said. “Then, the partnership becomes ‘loveless,’ and they start to love our customers more than us, no longer needing us.”

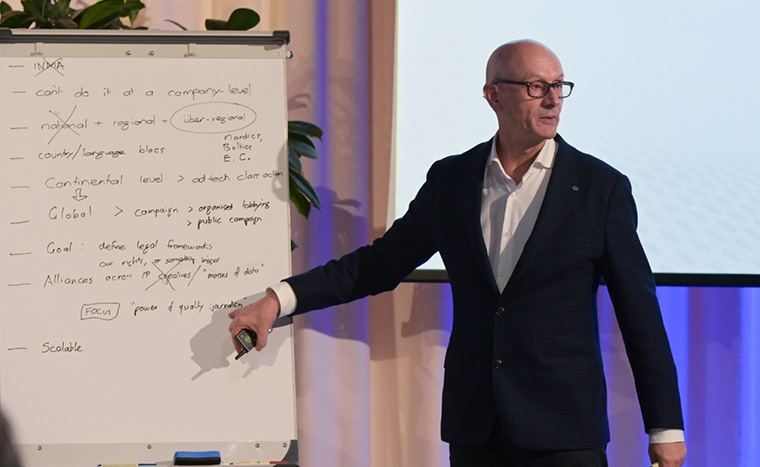

Whitehead emphasised that the media’s relationship with LLMs is yet another example of this pattern. There’s no legal framework for using media IP, no unified policy, and no regulatory or cohesive industry approach to guide these interactions. AI companies are selectively choosing only those deals with media outlets that suit their needs, while many news organisations settle for whatever compensation they can get.

The importance of data

Data is the key word when explaining the relationship between media and Big Tech companies.

“What Large Language Models need most, more than anything else, is a large dose of accurate, professionally created data,” Whitehead said. Despite the value media companies provide, AI companies often refuse to make deals, especially with smaller, local outlets. “We have something they need — quality content and verified archives that are valuable for training — but when we ask for a deal, they often say no.”

Only the largest players in certain language groups or markets secure deals, while others, particularly from smaller language regions, are left out. “They’re very selective. If you come from a small language group, like Finnish or Swedish, they’re not interested,” Whitehead said.

Such language groups could benefit from forming alliances with other languages from the same language group. By pooling resources, they could negotiate collectively and ensure that smaller languages are fairly valued. Such collaboration could also help establish shared legal frameworks and policies to protect intellectual property.

For smaller language groups, such as Swedish, it could be highly beneficial to form alliances with other Nordic languages. By coming together, these languages can combine their resources and content to negotiate collectively with AI companies. A unified language group could ensure that smaller languages, which might otherwise be overlooked individually, are properly valued. Additionally, this collaboration could lead to the development of shared legal frameworks and policies.

The solutions

So, what can be done? The key question remains: How do we ensure content creators are recognised and compensated fairly? The solution lies in technology, legislation, and organized collective action.

“One of the most important things we can collectively do is to find the next version of the business model for journalism, because that is the business model for democracy,” Whitehead said.

His words highlight the need of establishing a sustainable framework that not only benefits content producers but also secures the future of public information. Journalism, as a cornerstone of democracy, depends on the ability to generate revenue and protect intellectual property, especially as LLMs increasingly draw from these sources.

One problem the industry is facing is that it is difficult to define legal frameworks on a country level.

"Even if action at the country level is limited, we still need a sensible solution that goes beyond individual deals. It's about securing a two-way trade that recognises the value of journalism in the age of AI,” Whitehead said. “We need a scalable solution that protects the rights of content creators, because language models rely on verified, high-quality archives. This framework has to be future-proof, as these things keep constantly and rapidly evolving.

"The most important task right now is to get organised and establish clear legal frameworks. This isn't just about one company negotiating with AI firms — it's about ensuring journalism producers are financially recognised for their contributions."

In summary, while the promise of LLMs is undeniable, the path forward requires learning from past experiences with Big Tech and organising to ensure that content creators, especially in journalism, can ensure that their work is valued also in the future.

Changing the newsroom by changing yourself

"In every newsroom I visit, the number one question is: How do I get my team to do something they don’t want to do?" INMA Newsroom Transformation Initiative lead Amalie Nash told attendees at her Media Innovation Week breakout session.

Nash, alongside career and leadership coach Stephanie Grönke, laid out the framework for the group. They emphasised change isn't just about getting others to shift their ways — it’s about changing yourself as well.

As the media world continues to evolve — fueled by social media, digital transformation, and A I— newsrooms must adapt. Whether it’s adjusting attitudes, approaches, or perspectives, change is necessary to keep traditional, fact-checked journalism alive. “We need to ensure that the traditional media doesn’t lose its power. But how do you shift mindsets?” Grönke posed.

Grönke introduced a different method for achieving change in the newsroom: “Don’t expect a magic solution,” she warned. Instead, change starts from within — by transforming your own approach, you help spark change in those around you.

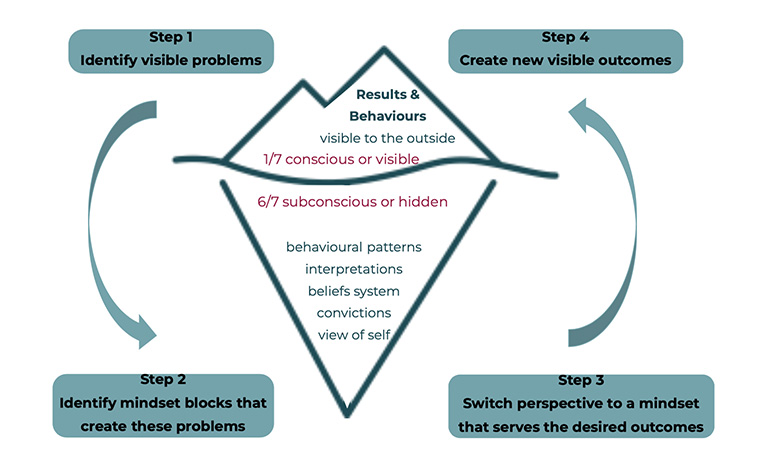

She introduced the iceberg model: Above the surface are day-to-day newsroom activities — disagreements, meetings, and decision-making. But it’s beneath the surface where the real transformation happens, encompassing deeper factors like behavioral patterns, personal values, and perspectives.

“This is where the real game-changer is,” Grönke said.

Participants are then asked to share challenges they face in their own newsrooms. Common issues emerge: the shift to digital-only, the rise of video content, customer focus, collaboration across brands, AI, and cultural shifts.

Grönke also emphasised the importance of mindset: “Why would I follow someone who has a negative opinion of me?” She stressed that if leaders or team members believe only others need to change, they are missing the point.

Nash and Grönke present a four-step guide for leading change:

- Identify the visible problem: Write down what’s not working and the desired outcome.

- Uncover the mindset blocks: Ask yourself how you feel about the people involved and why things are the way they are.

- Switch perspective to a mindset that serves the desired outcome: Challenge your own thinking. Get rid of "yes, but" excuses and consider the other side. Are your beliefs 100% true?

- Create new outcomes: What actions can you take to achieve the desired result? Commit to a change in the next two weeks.

By properly addressing steps 2 and 3, step 4 will naturally follow. It could be as simple as setting up a meeting, adjusting your schedule, or building stronger connections with colleagues.

To illustrate the model, Grönke shared a case study of a new CEO facing familiar challenges — overwork, constant interruptions, and limited resources. Beneath the surface, his issues stemmed from fear: “If I’m constantly busy, my team will see me as hardworking," or "If I change something, the company might fail."

Realising his fear of change and reconsidering his priorities and changing the perspective, the CEO empowered his staff, and even underperforming employees began to thrive. The internal shift made external change easier.

The workshop highlighted that sometimes the problem isn’t others — it’s us. We’re often quick to say “they need to change,” but in reality, change often starts with ourselves.